Testing mission, objectives and success metrics

Aug 8, 2022 by Rabih Arabi

What is the purpose and objective of testing?

Before performing any testing activities, it’s critical to understand the major aspects of testing. Sometimes a set of test activities fails to deliver any value to the business, even if it’s technically correct and functioning properly. As a result, we need to define the three primary elements of that stage: The test stakeholders, the test mission and the test objectives. Most of the time, stakeholders are not involved or even identified, making it difficult to determine how to align the testing process and strategy with something they value. It’s important to remember that testing shall cover both verification and validation — in other words, the test activities should assess what to do and how to do it.

We should work directly with each test stakeholder or a representative of that stakeholder group to understand their testing expectations and objectives. This might seem straightforward, but once the process begins, most stakeholders cannot respond to simple questions such as, "What are your testing expectations?" It’s likely the stakeholders won’t have thought about this in advance, at least, not in depth. Therefore, the initial response is usually along the lines of, “just make sure the system works well.” Of course, this is an unattainable goal due to two fundamental testing principles: First is the impossibility of exhaustive testing. Second is testing's ability to detect but not demonstrate the absence of problems.

As a result, the individual stakeholder’s quality needs and expectations should be discussed with respect to how far testing can realistically help the organization achieve its objectives.

A typical mission statement might look like this:

“To help our automotive OEMs and Tier 1s deliver a software product that meets or exceeds their end users’ expectation of quality.”

In this context, the word ‘help’ means to assist (cooperate effectively with) others involved in the software process to deliver software quality. The goal here is to make software quality a team goal not just the testers' responsibility.

Whereas, mission statements like this should be avoided:

“To ensure that our customers receive a software product that meets or exceeds their expectations of quality.”

This mission statement is flawed in two ways: It ignores software development and maintenance (as well as other team members) and reduces software quality to a testing issue. Also, it uses the word ‘ensure’ which, in this context, means making certain that customers and users are satisfied, if not delighted with the quality of the software. However, testing is an important component of a larger quality plan, but it can’t guarantee quality on its own.

Given an achievable mission for testing, we can set objectives to help us realize it. While the objectives may vary, we usually consider one or more of the following, or any other applicable objectives based on the project requirements and nature:

Find critical defects — critical defects significantly undermine customers’ or users’ perception that their quality expectations had been met (i.e., defects that could affect customer or user satisfaction). Finding defects helps by providing information which can be used to fix defects before release.

Find non-critical defects — while the focus of testing should be on critical defects, there’s also value in discovering defects that are merely annoying, inconvenient or productivity draining. Even if not all non-critical defects are fixed (which is frequently the case), many can be identified. After-sales, customer service, or help desk staff can resolve production failures and reduce user frustration more effectively, especially if the test team discovers and documents workarounds.

Manage quality risks — while testing can’t eliminate the risk of quality problems, it does reduce the risk of undiscovered defects. We can achieve the highest level of quality risk management by selecting tests that relate to the most critical quality risks. The greatest degree of risk reduction is achieved early in the test execution period if those tests are run in risk order. A risk-based testing strategy like this enables the project team to achieve a known and acceptable level of quality risk before putting the software into production.

Build confidence — organizations, and particularly senior management, dislike surprises. After completing a software development or maintenance project, they want to know that the testing was adequate, the quality will satisfy customers and users, and the software is ready for release. While testing can’t provide 100% certainty, it can provide important information that gives the team an accurate sense of how confident they should be.

Generate information on the item under test — testing takes place within the context of the development and maintenance project and must meet the needs of project stakeholders. This entails collaborating with those stakeholders to develop efficient and effective procedures, and service-level agreements, particularly for processes involving hand-offs between two or more stakeholder teams.

Test managers must collaborate with relevant stakeholders to establish reasonable entry criteria and quality gates when work products are to be delivered to or from testing. The gathered information can be used for a variety of purposes, including: Improving test cases when shared with the test team; leveraging the information to remove defects; increasing code quality; learning to create better code; and making better decisions based on the provided information. All of these actions lead to better and higher product quality.

Aside from the testing mission and objectives, the test policy should define how testing fits within the organization’s quality policy, if there is one.

If no quality policy exists, it's important to avoid referring to this document as a ‘quality assurance policy’, because testing can’t guarantee quality on its own, as highlighted earlier. Apart from that, quality assurance and testing are not the same, but they are related; a larger concept of quality management ties them together.

Before defining any metrics, we need to understand why we define them and how to use them appropriately. Any test manager first defines the test goals, as testing aims to achieve test objectives. The team must develop a way to measure objectives (metrics) to evaluate whether they’ve been met.

Using metrics that aren't aligned or tied to test objectives is ineffective and could harm both the team and business. We all know that not having defined goals, destinations, objectives, or success criteria is a major issue. This type of uncertainty is one of the leading causes of business failure, team demotivation, and in certain circumstances, even career termination.

Measuring where we are now can help us figure out how much further we need to go to reach our objectives. Test managers must be capable of defining, tracking and reporting test progress indicators.

We all agree that different projects have different requirements, setups and circumstances, therefore they tend to have different test objectives. This is the main reason we can’t apply one set of metrics to all projects. As a test manager, the first step you should take is to define the related objectives, align them with the stakeholders and make sure they’re documented in the test plan. It’s crucial that they are considered in the testing definition of “done”.

After defining the test objectives, a set of related, reasonable and applicable metrics should be defined to measure the testing efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction. This helps provide insights into the test status of the project and supports decision-making for the defined test objectives. We should understand that metrics are only indicators and we shouldn’t work toward fulfilling them. This is because defining these metrics is massively affected by the overall project conditions, the team, organizational behavior and dependence on other teams (requirement, development, etc.) and so on. Therefore, the test manager should be careful while defining test metrics, planning them properly and monitoring them continuously to avoid any unintended side effects.

Let’s take one example of test objectives and related test metrics:

One of the major testing objectives is finding defects. It’s crucial to emphasize the importance of the correct formulation of the objectives. As discussed earlier, the objective is to “find defects” not “ensure software product quality”, since performing test activities can’t assure quality. As testers, we rather assess and help customers, developers, product managers and others, to provide a software/product that meets or exceeds their expectations of quality.

The first simple effectiveness metric measures the defect detection rate (DDR) (i.e., the ratio between the occurrences of the detected defect and the total number of defects). Another effectiveness metric is the percentage of detected critical defects, or the ratio between the number of detected critical defects and the total number of defects found.

The efficiency of finding defects can be measured by using the percentage of rejected defects (i.e., the ratio between the number of rejected defects and the total number of defects). A customer survey can help measure satisfaction, while an internal survey measures team satisfaction with the test process and other workflows. A set of methods and tools support the initiation of surveys (e.g., IBM, HP and so on).

Various departments within the organization can help set up a customer survey. Here’s the procedure for running a survey (for internal use):

Testing metrics can be classified as follows:

Metrics allow testers to report consistently and enable the coherent tracking of progress over time. Test managers are frequently required to present results to stakeholders, ranging from technical staff to executive management.

Also, because metrics can be used to determine the overall success of a project, great care should be taken when deciding what to track, how often you report it and the way you present the information. The test manager shall consider the following:

These are the test-metric stages:

It’s impossible to define all possible metrics, so we should start with what we want to achieve, making sure the metrics are simple, relevant, and easy to interpret.

Here are five steps to help you define your metrics:

Keeping these factors in mind leads to the creation of more helpful metrics. If suitable project decisions can’t be made based on reported metrics, they become a pointless exercise. The goal question metric (GQM) approach takes a set of goals identified by the department or project and indicates a way to assess the achievement of those goals. This consists of a sequence of data per question to answer each question quantitatively to assess performance. Metrics are often reported daily, weekly or monthly. So, any solution that can generate and distribute reports while relieving test managers and test engineers of tiresome, repetitive activities, should be considered.

The test process, a crucial part of successful testing, is often underestimated. Measuring the three main aspects is easier said than done, but we need to understand why we define them and the appropriateness of their usage.

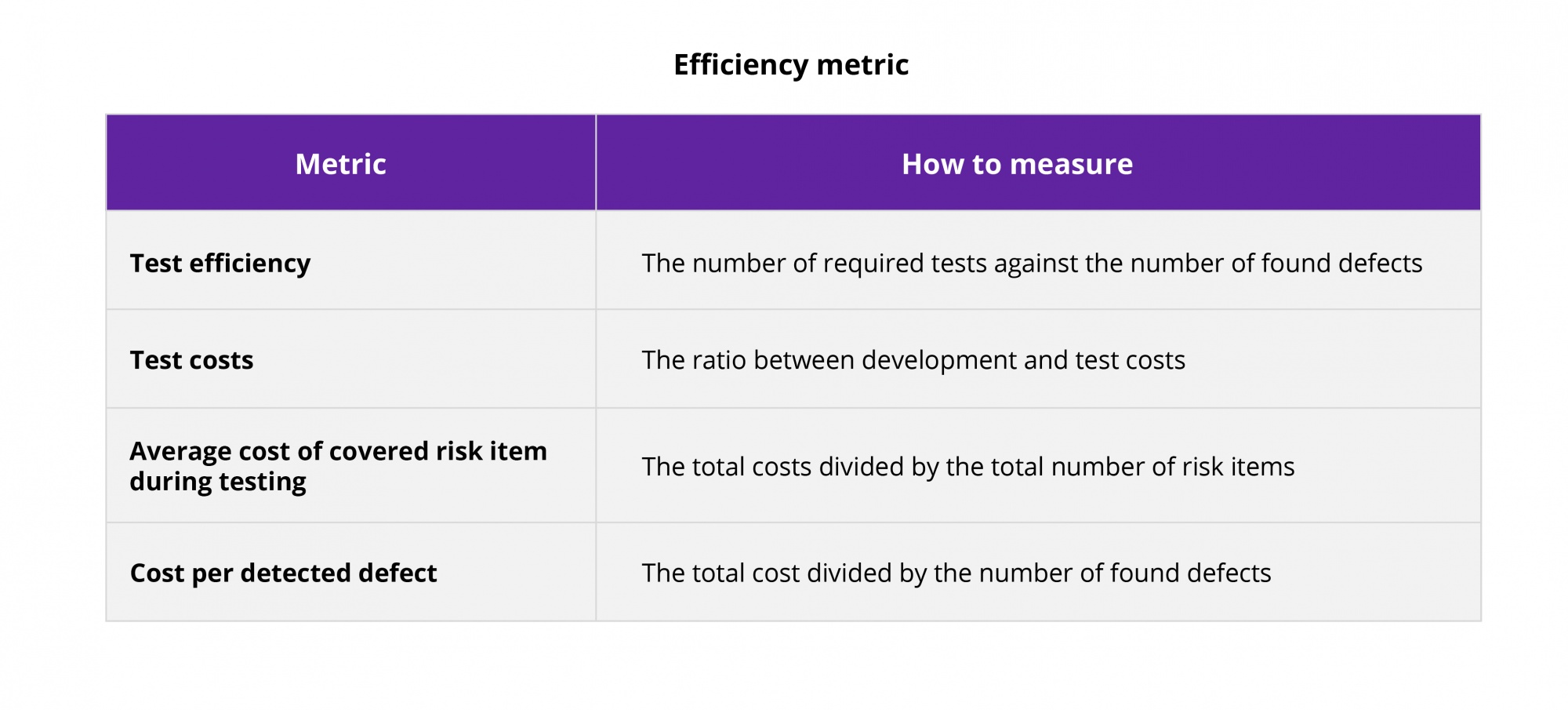

Here are some definitions of efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction, including ways to measure them:

The examples of metrics and how to measure them shown below are not the full extent of possible metrics — that depends on the project scope and goal.

Sources: ISTQB Expert Level © 2013, RBCS, ISTQB Foundation level, ISTQB Advanced level